You Are Here: Mapping the Spatio-Temporal Phenomenology of Heterotopic Play-Spaces

Ammo. pick up. left pointer;aim right pointer;shoot;kill left pointer;reload loot. sound … crouch. Crawl. peek? Slowly, quickly, your thumbs drag across joysticks and pixels accommodate. You are here. Right now. Turn. You are here. Right now. The code tells you this. Your life is in danger. Your nerves are ones and zeroes. Need ammo. /time set day The sun came up. The code says this. The code is speaking. You answer. Can you feel it?

When you game, a world is born that is all your own, a space of intensity and transportation; we reset, rewind, wind down, and power up through our embodied experience of gaming. So how do we talk about this space which can only be observed through immediate experience? I suggest that we open our methodological inventories and equip phenomenology. Phenomenology is the philosophical movement which prioritizes the understanding of lived experience through raw textures and sensations over the detached, objective approaches of scientific or theoretical analysis. As Maurice Merleau-Ponty states in his seminal work Phenomenology of Perception, “Phenomenology is only accessible to a phenomenological method… Phenomenology involves describing, and not explaining or analyzing,” (1). In short, phenomenology is about what you feel, see, hear, and taste; the raw, real, sensory data which shapes our understanding of ourselves and the world. With this in mind, I aim to map the gaming experience as inhabiting a play-space which houses both the world of the player and that of the game. This play-space creates a particular phenomenological experience for the player, giving them the chance to experience new relationships with space and time.

Now that we have employed our sensory method, we might now equip a heterotopic framework. It’s dangerous to go alone, after all. In his paper Of Other Spaces, Foucault outlines his concept of heterotopia, a space that is fundamentally other, through the course of six principles. The first states that there is “probably not a single culture in the world that fails to constitute heterotopias,” (2). The second principle is that, as cultures evolve, these heterotopias adapt to fill different roles. As video gaming continues to grow as the largest entertainment industry in the world, it is obvious that they continue to serve an important role to consumers worldwide. They adapt to accommodate new forms of technology which provide new phenomenological opportunities, such as haptic feedback vibrations or the nightmare of virtual reality zombie games.

The third principle states that the heterotopia is “capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible,” (3). This is true of the space that is created and inhabited when gaming. I am not fully present with all of my senses in my own space, and though I feel immersed, I am not fully present in the world of the game either. Paul Martin outlines the idea of the “playing-space” in his paper, A Phenomenological Account of the Playing-Body in Avatar-Based Action Games. The play space is fundamentally heterotopic in the way that it juxtaposes the IRL and the digital. As Martin says, the playing-space constitutes “the total space that comes into being in the moment of play and is inhabited by both player and game,” (4). The playing-space is created when the two worlds are present at once, and the grid of pixels begins to sprout roots into my living room floor.

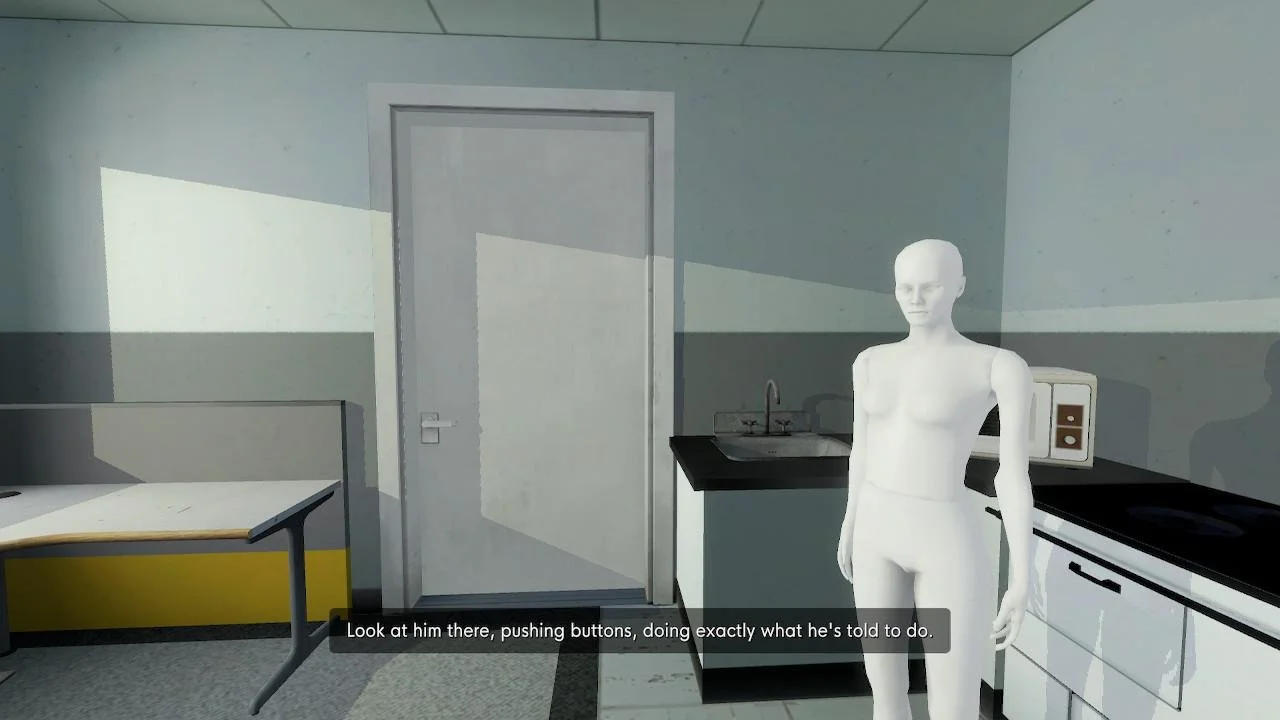

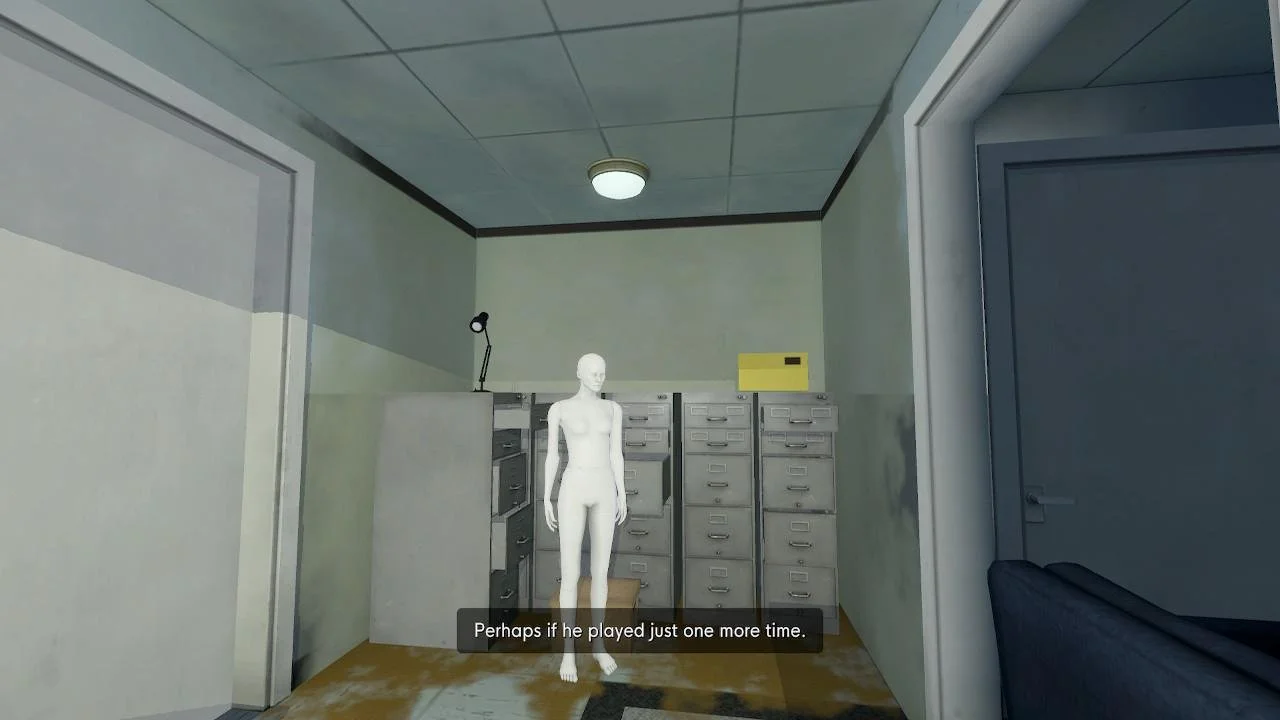

Foucault’s emphasis on these juxtaposed spaces being otherwise incompatible reminds me of the delineation we tend to draw between the real and the digital. This could be exemplified by something as simple as the idea of the acronym “IRL,” which in its very existence both presupposes a border between one’s “real” life and one’s screen life. It is imbued with an assumption that the texture of our experiences in the real are more immediate and pure, but which exists by way of this other, more ephemeral life. Culturally, video games have always been steeped in this idea of otherness. My living room couch does not feel like the neverending series of yellowed rooms and empty desks that make up the space of The Stanley Parable, as its narrator reminds me that turning off the game will be the only real decision I could ever make. But somehow, I still believe her and feel she is addressing me. I still feel the immediacy of her words as a regulatory force in my life; she is my boss, my parents, my god.

The fourth principle touches on the heterotopia’s temporal identity; “The heterotopia begins to function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time,”(5). The heterotopia is enrobed in a particular expression of time, where time is both infinitely accumulated and immediately suspended. This is what Foucault terms a heterochony. As we play, we arrive in our bodies at that break in time, and often stay there until reminded by some external catalyst; a roommate, a window, a church bell. In a study done on the phenomenology of gamers, one subject stated: “Say, I was completely absent; I experienced nothing but the game,” (6). Our experience of time is ruled by the game, which hands us the tools to do our own time-shaping. Speed becomes the currency of modulated time, and we use the game’s mechanisms to inflate and condense it. We are often interested in going faster, cutting away at travel time through game mechanics like teleportation (/tp) or diegetic modes of travel such as Breath of the Wild’s paraglider or Red Dead Redemption’s horse. We can choose to only engage in dialogue that gets us somewhere, trimming the metaphorical fat, while still spamming B to ingest the dialogue we do engage in at a faster rate. Cutscenes condense historical information and storylines into compact and easily digestible bits of information. There is an entire pocket of game culture which is interested in speedrunning, wherein the most advanced time-shapers subscribe to a method of intense heterochrony. Some games do have time-slowing mechanisms, like Red Dead’s Dead Eye, which are often employed to enhance the player’s performance in combat. Simultaneously, the game accrues data on the player; how long they have played, how many times they have saved, what time they last saved.

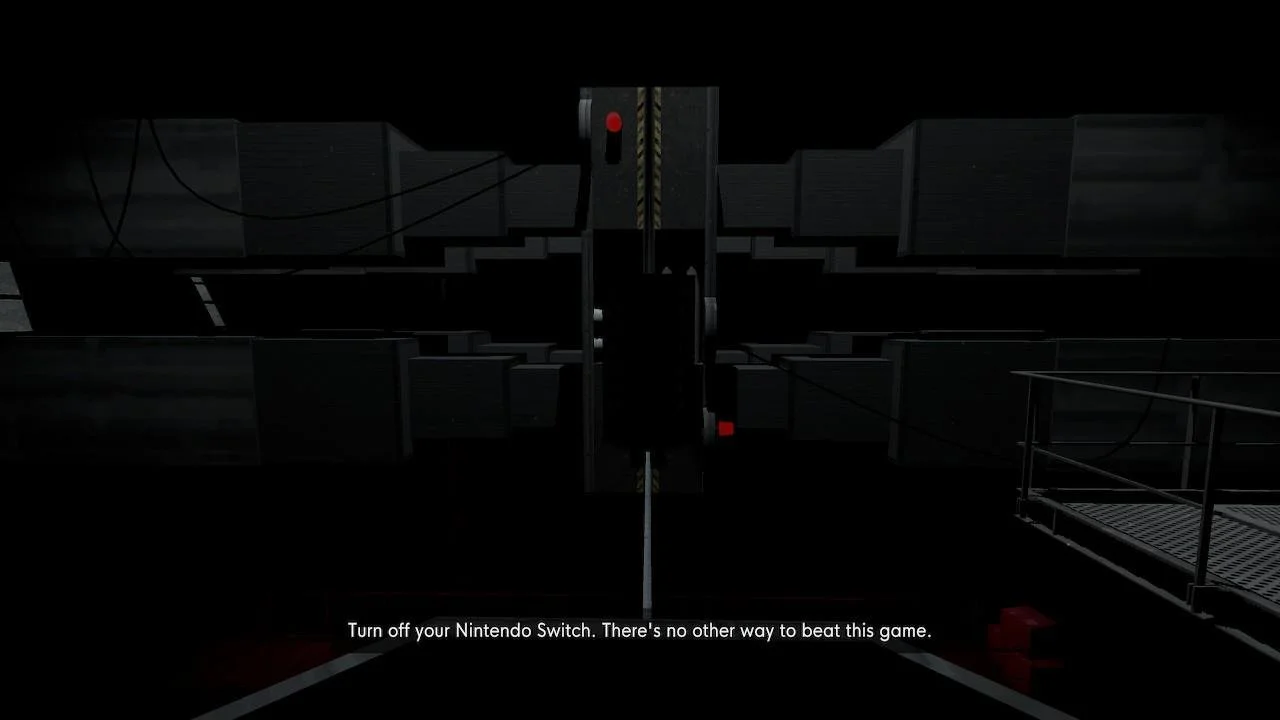

The fifth principle of the heterotopia is that “Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable,” (7). As an occupiable space, the heterotopia requires certain rites and rituals to be accessible to those who wish to occupy it. There is a system of governance present, which presents in this case as the governing code that builds game worlds and creates systems of possibility and allowance. The code tells us how to walk, jump, aim, shoot, pay respects; game mechanics which are outputs of specific inputs and cannot be attained any other way. It tells us how and when we can perform certain actions, who we can kill, how fast we can go and how far we can run. This programs us to internalize a system of inputs which we must perform to get whatever outcome we want from the game, and these become habitual the more we play.

In his text, Merleau-Ponty expands on frameworks of consciousness, revealing a pre-reflective organization of time, space, and sensation that is intrinsic, instinctive, and anticipatory. Just as we can anticipate the texture of an object, we project spatial and temporal expectations onto our experiences before they are fully realized. These expectations map themselves onto the body through systems of habit. Even as I write this, whenever my left hand comes to rest I find my first three fingers on the W, A, and D keys, my body forever primed to play Minecraft. If we can understand our experiences of time and space as being pre-emptive and projected, we can then assume that we operate within the same anticipatory structures when immersing ourselves in a world that is different from ours.

As we move through video games, our pre-reflective systems reorganize themselves around the limitations and needs of the space, and the video games in turn inhabit us. Paul Martin elaborates on this idea of the game “embodying the player”8 through his concept of the playing-body. He builds off of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenal body, who inhabits not only the immediate or ‘objective’ body but all of its associated parts and accessories; “a woman may, without any calculation, keep a safe distance between the feather in her hat and things which might break it off. She feels where the feather is just as we feel where our hand is,” (9). Martin defines his playing-body as “the Merleau-Pontean phenomenal body as it exists and changes during play… the playing-body arises through the player-game interaction and comes into existence in the moment of play, ” (10).

In the moment of phenomenal habit, the body is primed through its systems of pre-reflective organization, which are in turn shaped by the hegemony of the game and its code. This nods to what Foucault calls the docile body, through which “calculated constraint runs slowly through each part of the body, mastering it, making it pliable, ready at all times, turning silently into the automatism of habit.”11 The docile body is one that is trained by a system of constraints through the implementation of habits as an input with a necessary output. Pressing A to pick up a virtual item becomes a gesture as familiar as scratching an itch. We are left with a three-headed body; one that is instinctual and anticipatory, present in all of its limbs (whether sanguine or cybernetic), and controlled.

Foucault’s final principle is that the heterotopia serves a function “in relation to all the space that remains,” (12). This is either through the heterotopia of illusion, which makes illusory all other places through a reorganization of the real; or the heterotopia of compensation, another real place which is “as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled,” (13). As heterotopias of illusion, games such as Bioshock reflect on real world ideologies and phenomena, giving the player the opportunity to be embedded and embodied in a real socio-political commentary.

Simultaneously, they give us the chance to “game-ify” our lives by recreating game mechanisms and ideologies in the real. This is exemplified through linguistic trends like calling people NPCs, but extends into much more consequential phenomena like the design of dating apps. Phenomenologically, we might begin to form certain associations with objects in games which now hold a different significance. For one, I can’t see a pinwheel without feeling the rush of excitement about finding a Korok. Alternatively, as heterotopias of compensation, video games offer the comfort provided by the perfection of the code, functioning as a flawless counterpart to our messy lives. Everything in a video game has been placed there with intent, and we can relax into our docile playing-bodies that need only know how to press A to get what we want. The code answers all questions, we need not worry about the mess of life decisions, paperwork and resumes, dishes and laundry.

“Thus, gamers reported that with an entry into a video game, the real world ceased to exist, and the gamer became absent and relocated into another world, a world that exists while there is a game,” (14). Next time you return to inhabit your play-space, notice the ways that your body has become something else. Your hands react before you need to think. Time glides through and around you. The limits of your movement are governed by a new set of rules. If you fall it will never hurt. You feel only the current of the console breathing life into you, caressing you, teaching you. You’ve made it to your own playground, a space that is entirely and exclusively yours. Leave behind your tangled life, its breaks and knots, and come into your jungle of electric ropes, where you can swing freely, feeling.

Citations

1. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Donald A. Landes (London: Routledge, 2012), lxxi.

2. Michel Foucault, "Of Other Spaces," trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 24.

3. Ibid., 25

4. Paul Martin, "A Phenomenological Account of the Playing-Body in Avatar-Based Action Games," Ludic Journal 1, no. 1 (2019): 1.

5. Foucault, "Of Other Spaces," 26.

6. Benjamin Čulig, Marko Katavić, Jasenka Kuček, and Antonia Matković, "The Phenomenology of Video Games: How Gamers Perceive Games and Gaming," in Engaging with Videogames: Play, Theory and Practice, ed. Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans (Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2014), 69.

7. Foucault, "Of Other Spaces," 26.

8 Martin, "A Phenomenological Account of the Playing-Body," 2.

9 Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 165.

10. Martin, "A Phenomenological Account of the Playing-Body," 2.

11 Michel Foucault, "Docile Bodies," in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 179.

12. Foucault, "Of Other Spaces," 27.

13. Ibid.

14. Čulig et al., "The Phenomenology of Video Games," 69.